After leaving Laverton, we relocated 90 miles back to Leonora, back to the sealed road. There was no nickel find in Leonora, but the town was a hub for rail and road traffic to the north and east. The railway stopped at Leonora, from Kalgoorlie in the south. Nickel from Mt. Windarra to the east was trucked to a railway siding in Malcolm, a dot on the map between Leonora and Laverton that was once a thriving gold-mining town. Nickel was also trucked to Leonora from Leinster to the north. Leonora existed as a Shire seat and hub for the sheep and cattle industry around it. Nothing grew out there. Leonora’s population during the 1970s was somewhere about 1,000. Someone might even look at that number and consider it overly generous. It was, though, the biggest town around; the next largest was Kalgoorlie 150 miles south.

Leonora, 1899. On the horizon is Mt. Leonora, named in 1869 by explorer (and Western Australia’s first Premier) John Forrest after a relative. Gwalia is to the right of the hill.

Two miles south of Leonora, off the main road, sits the ghost town of Gwalia. The name “Gwalia” is, as far as I can tell, an old Welsh word for Wales. The town emerged from the desert mostly as a shanty town, home to miners working the Sons of Gwalia gold mine. The “Gwalia” was a major find in the area, established in 1897, and grew to become the largest gold mine in the state outside Kalgoorlie. Leonora was established up the road from the mine, into a normal looking town with regular streets and commerce, while Gwalia started out as a mix of shanties and huts arranged in no particular order. There was a rivalry between the two towns, such that Leonora wouldn’t recognize Gwalia as a “town,” but finally had to gazette it as such in an effort to control a rampant growth of unregulated saloons (called “sly-grogs”). The state’s first government-run hotel was opened in Gwalia in 1903, and still stands today as a popular photo subject.

The “Pink House,” a miner’s shanty typical of the sort built in Gwalia, mostly from corrugated metal, wood and hessian for walls. The house is small; most people have to crouch down when walking inside.

The Gwalia State Hotel, built 1902; a popular tourist attraction today from the outside only (the building is closed to the public).

Back in 1897, when Kalgoorlie and the surrounding Great Victoria Desert was abuzz with gold-seeking activity, there were a few larger companies looking to stake a claim. One of them was a British company, Bewick, Moreing & Co. They hired a young American geologist by the name of Herbert Hoover to travel into the West Australian scrub and represent their interests. He made a few moves around Kalgoorlie and eventually took management of the Sons of Gwalia mine. Part of his strategy was to hire mostly cheaper European workers; the town of Gwalia became a melting pot of Poles, Italians, Czechs and Slavs, among others. Hoover built a house here which still stands and operates today as a bed & breakfast and museum. Hoover was soon called away by his company to explore interests in China, and of course eventually went on to do a few other things around the world, including become President of the United States.

Hoover’s house in Gwalia, currently a bed and breakfast.

http://www.gwalia.org.au/hoover-house/accommodation/

The Sons of Gwalia mine operated almost continuously until December 31, 1963. Practically overnight the town emptied, dropping from several hundred to a few dozen. Buildings and shanties were abandoned, and for almost a decade most stood silent, succumbing to the heat and dust of the desert. During the early 1970s and on into present day, restoration efforts got under way to preserve the few significant structures left behind.

When we arrived in Leonora, we somehow ended up taking residence in one of the abandoned houses on Manning Street, Gwalia. It wasn’t a shanty, but a more substantial structure built to normal scale, but it was still in need of considerable reconstruction. The way I understood it, Dad purchased the house from the Shire for $50, on the proviso that he bring the house up to code. When we moved in, there was no running water, no electricity, and the toilet was the standard Aussie dunny (outhouse) up in the corner of the back yard. This was 1971 (give or take), so there was also no television. The only telephone available to us was a public phonebooth up on the main street, Tower Street, outside the old Mazza store building (long closed and boarded up).

A standard old house in Gwalia, an upgrade from the shanty. Our house was this style, albeit in somewhat better shape. I don’t have a photo of it, as it is still occupied today. The road in front is Tower Street, the main drag through town. To the left (quarter mile) is the mine, and to the right (two miles) is Leonora.

The house was a standard structure with typical layout: across the front was a verandah. You would step in to a hallway that ran the length of the house. The first room on the left was the living room, and on the right, a bedroom (which became Mum and Dad’s). Further down on the left was the kitchen, and on the right, another bedroom (which became mine and siblings that came later). You would step out from the kitchen into the back “patio” area; on the left was the bathroom and beyond that, the laundry. Next to the bathroom was an open room which became one catch-all for Dad’s crap (he had more than one). Once outside the laundry, you were in the backyard, with not a scrap of green grass anywhere, just dirt. Out here clothes were hung out to dry.

The main four rooms of the house were done up first to make habitable; Dad did up the main bedroom in plaster, which kept it relatively cool in the 100°+ heat. The living room and kitchen were opened up to become one large room. My bedroom was largely untouched. The floors throughout were wood, and walls were flat sheets of fibro cement, except my room, which had the original hessian wall coverings. This was a standard material used in the early days, painted over to stiffen the material and make it look half presentable. I had a window out to the side, which I made a habit of climbing out of to scurry away somewhere, until it got nailed shut.

The kitchen had a wood stove with cast-iron top, standard for the old days. The living room had a fireplace, topped with a tin tube chimney. Once we got water supply to the house, it would have to be heated on the stove or fireplace for a hot water bath, laundry or dishes. For lighting at night, we had carbide lamps, the same kind the miners used in the depths below. The smell is fresh in my mind to this day. We also had kerosene lamps, and the refrigerator was an old kerosene-powered kind.

Dad was quite handy with things mechanical, and managed to get an old Crosley engine to work. The thing was an ancient cast-iron block with the top open for fuel, and large flywheels on both sides. To start it, a crank handle was inserted into the hub of the flywheel and turned with all might and strength, in hopes that a single POP would cause the engine to catch and fire up. A belt ran from the engine to a generator to bring in a meager supply of power. There was a certain comfort lying in bed at night listening to the random POP and chug of the old engine. Eventually power from the town supply was fitted to the house.

Water still had to be heated the old fashioned way, on the stove or fireplace. The bathroom was a ramshackle room with little privacy and too much ventilation to the outside, with holes in the walls and roof. The bathtub was a leaky old tin kind with feet, similar in look to the old-style ones that seem to be all the rage these days, but not near as charming. Dad had to try to seal up the leaks on a regular basis, which left little beads of tin along the seams, poking your behind and making the experience very uncomfortable.

Eventually Dad built a boiler alongside the house near the back, encased in brick. We would scour the old building sites around the town collecting bricks, chipping off the old mortar. The kind of mortar they used in the old days was flimsy at best, breaking away from the brick with little effort. It was one of my chores to set a fire inside the boiler and get the hot water going. The water wasn’t connected to the house supply, so if you wanted hot water, you had to go to the boiler to get it.

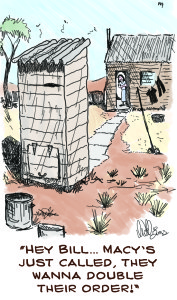

The toilet was the old outhouse kind, the dunny as it is known in Australia. The weatherboard structure with corrugated iron door was not a comfortable commode, the inside reaching well above the 100° temperatures outside. You would simply get in, do your business, and get out. I could sit there and watch the redback spiders in the corners. Dad would spend forever in there, reading, despite the heat.

Below the bench was the collection bucket, accessible from behind the dunny. Once a week the town outhouse collection service would be by to remove the full bucket, load that up onto the back of the truck, and put an empty one in its place. Dad referred to him as the “turd burglar.” It must have been a thankless job.

I draw from time to time. More on that later.

I didn’t seem to mind chatting to the guy until he had to move on. I was quite a chatty kid in the beginning, talking up a storm to anyone who dared listen, without much mind to whether they were keen or not. I got that from Dad, without question. He could talk paint off a wall. He was opinionated and knowledgeable, never wrong about anything, an expert on everything, and he would talk away at some poor sop until either both got hungry, wives were fed up, or the sun had disappeared. I might have been a talker as a young kid, but having to sit around and wait for the old man while he yammered on was torture. Funny though that if I chatted up the turd burglar, I’d be scolded and told to leave the man alone.

Eventually the day would come when the dunny would be retired and an actual flushing toilet had to be installed. It probably came about as a result of a few coinciding factors: the retirement of the turd burglar service, constant pressure from Mum to quit making her use the dunny, and code upgrade requirements. A septic system had to be put in as there was no sewer service out there. The new outhouse, a modern, slightly-larger kind, was built at the back of the house. It was large enough to accommodate a shower, which was essential since everyone was tired of getting their butts punctured in the bathtub.

The shower was set up before the toilet was functional. It was a pull-chain kind, basically a filled bucket hoisted up to the ceiling, used sparingly by pulling a chain to release a dose of water. Along with firing up the boiler, it was my job to fill the shower bucket before use. If Mum or Dad were in the shower, I’d have to stay close by in order to pass a full bucket of warm water through the partially opened door. The shower would be filled, then hoisted up and tied off.

Putting in a septic tank turned out to be harder than anticipated. The ground out there in the desert is rock hard with little to no topsoil. Dynamite was required to loosen the rock. It took weeks for Dad to finish digging the hole and putting the tank in.

One of the strangest things we ever encountered happened when Dad was digging the septic tank. Buried a few inches underground was a seemingly perfectly preserved fruit cake, the Christmas kind that traditionally gets passed around but no one wants. It was a mystery as to how the cake got there, and for how long. The house had been vacant for years before we came along, so it had to be there for at least seven or eight years. Plus, it was under some inches of rock, still in its plastic wrapping. While everyone pondered its existence and origin, the dog gladly wolfed it down, with apparently no ill effects.

The day came when finally the septic was in and the toilet was ready for use. Behind the toilet, standing high above, was the vent pipe. On top of the vent pipe was supposed to be some sort of cap, and there it was sitting on the ground. The toilet was incomplete without that cap inserted into the top of the vent pipe, and the pipe was firmly installed and not coming out. The answer was to have me climb up on Dad’s shoulders while he stood on the roof of the toilet, and I would reach up and slip the cap into place. The procedure went without a hitch, but I can recall every moment of it, panicked as I held on to the pipe with nothing between me and the ground, which I was reminded not to look down at (I did).

The last little tidbit about the toilet involves pumpkins, which began growing behind the toilet, evidently fueled by nutrients from the septic tank. We had no problem chowing down on these pumpkins, but there was one night when Dad took a bite into a slice of pumpkin and immediately spewed it out in disgust. Either he suddenly realized where it had grown, or perhaps there was more nutrient in it than normal. It’s hard to say, since I had no trouble with it. From that day forward, Dad never touched pumpkin again, of any sort, from any location, on any plate.

Next: An in-depth look at the town of Gwalia (my playground), and its inhabitants.